Firing up the next generation

Young potters in the ancient heartlands of ceramic industry are carrying forward the craft of celadon-glazed porcelain production, Deng Zhangyu and Ma Zhenhuan report.

On an early August morning, craftsman Zhang Xi drove his car quickly through the twists and turns of a mountain road in Longquan, Zhejiang province, hoping to reach his destination — a century-old kiln — as soon as possible, where hundreds of pieces of pottery that had been given their final celadon glaze were finally ready.

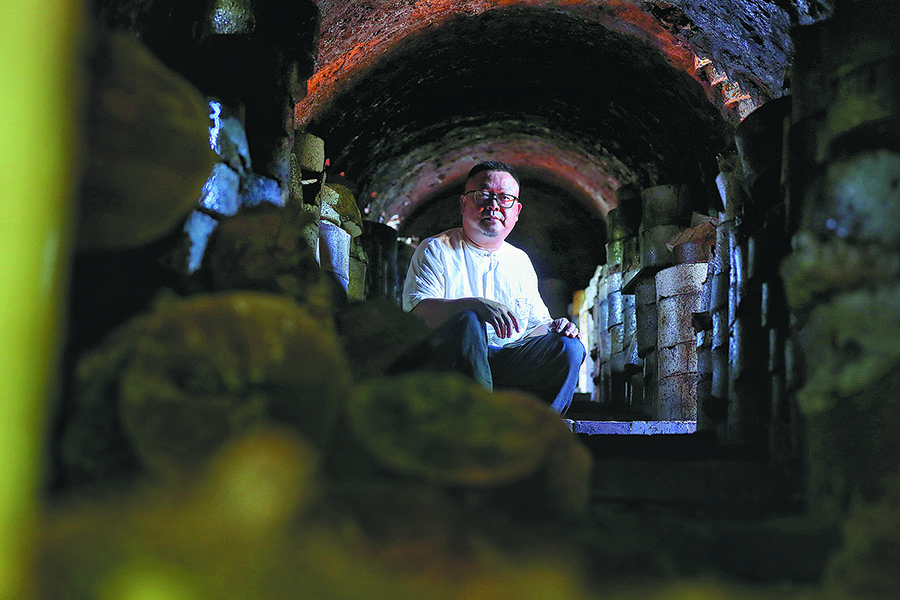

The 51-year-old craftsman has used the old kiln, which is nestled on a mountain near Xitou village, for many years. Every time he removes his creations from the kiln, seeing them in their finished celadon color remains as exciting and nerve jangling as ever.

"It's like opening blind boxes. The same formula of glaze applied to different vases can look totally different on each one," says Zhang.

Potters work at a kiln in Xitou village in Longquan, Zhejiang province. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Their colors usually fall in the spectrum between lavender gray and plum green. Sometimes though, they turn out brown or yellow. All these colors depend on temperature changes during the two-day firing — a process described by local craftsmen as "a song of clay and fire".

The traditional firing techniques of Longquan celadon pottery, which dates back further than 1,600 years, was included on UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity List in 2009.

An experienced craftsman, Zhang began learning about making celadon-glazed pottery in a wood-fired kiln from his grandfather at the age of 18. The craft has been passed down through his family since the 18th century.

Many families in the village, like Zhang's, made their living from the traditional craft for centuries, but with the introduction of gas kilns in 2000, a technology that allows and ensures exact temperature control to produce porcelain with a high-quality glaze, use of traditional wood-burning kilns began to disappear.

"Gas or electrical kilns can ensure the quality of the celadon glaze. Craftsmen can predict what they get from modern kilns, as long as they set the right temperature. However, traditional kilns can offer unexpected surprises, which enamors makers and lovers of the craft," says Zhang, walking alongside the kiln, which is made of brick and clay and is more than 20 meters long.

He checks the temperature of the cooling kiln by touching the bricks, and is able to judge when it's the right time to remove the porcelain treasures inside.

The long kiln, shaped like a snake, can house dozens of vases or hundreds of tea cups. It takes 5,000 kilograms of wood and 12 potters to keep it firing for two days — a high cost in "both time and energy".

Celadon master artisan Zhang Xi in Longquan. [Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

"Every brick kiln has its own personality. This one is very mild and tender, and the color of green it produces is light," Zhang says.

He points to another one standing in front of the village, which in his words is "fierce" and its products are heavy in gloss. A good firing needs half a year of preparation.

After many firings, a craftsman knows the kiln inside out, and learns how to control the precise temperature by watching the color of the flame, or by using a piece of clay as a measure. The heat can reach as high as 1,310 C.

No matter it's a brick kiln or a modern one, the craftsman's aim is to pursue a glaze of exquisite beauty, with their own unique input.

"Just like a chef, we have our own formulas to produce different shades of green, a color similar to jade," says Zhang, adding that they can expertly identify the various shades of green by eye.