Artist creates precious canal memoirs on canvas

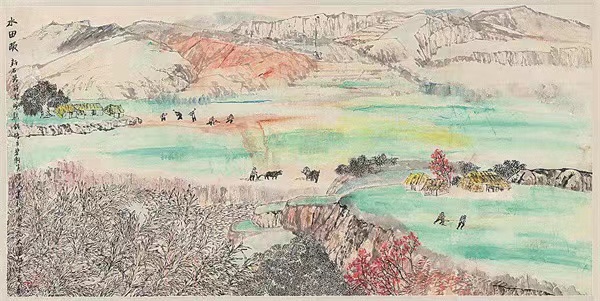

An ink paintings by Wu Liren reveal the natural landscape and urban development along the Grand Canal in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Painting is just another way of keeping a diary, so said Spanish artist Pablo Picasso whose irrepressible genius spanned nine decades. Wu Liren has been maintaining such a "diary" of the Grand Canal for more than 40 years.

The 65-year-old painter from Hangzhou city, Zhejiang province, has used ink and brush since 1978 to capture the beauty of the arterial waterway, the intrigue of the alleys that scurry along its liberal length, the hospitality of local residents and the richness of culture that flows all the way.

Wu says memories and emotions run deep in his paintings, and these are far more important than any technical perfection.

"My art has always been about the Grand Canal. Sometimes I paint what I saw in the past and sometimes I reproduce what I heard about people who lived by the canal," he says.

The artist recalls how Tomb Sweeping Day seemed like a big waterfront celebration when he was a young lad. Not only did residents gather at the shrines, people from neighboring places joined the temple fair in Hangzhou.

His memory of boats surging back and forth at the crowded wharfs is still as fresh as newly applied paint.

Wu remembers how villagers often had a flower strung to a white towel wrapped around the head. Some wore long green-and-blue aprons and some sported yellow cloth bags on their shoulders. All of them made perfect subjects for his paintings.

The main businesses along the canal were fabric-dyeing, brewing and making joss paper. Dozens of temples along the canal in Hangzhou were crowded during the fair.

An ink paintings by Wu Liren reveal the natural landscape and urban development along the Grand Canal in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Ordinary days were memorable as well. Wu says people back then called the canal "the moat". Since there were no guardrails, fun activities were common.

"In sultry summers, we would make a splash in the canal, swimming for hours and catching shrimps, snails and clams," he recalls.

Life was blissfully simple and everybody in the neighborhood knew one another. Wu's grandfather, who ran a shoe business, owned a house with a big living room. Every day after lunch, some of the old man's friends would drop by for idle chitchat. Their lively anecdotes inspired Wu, barely 10 years old then, to re-create the grandeur of the canal on canvas.

Besides his grandfather's friends, there were many others who shaped the young boy's imagination. A veteran, who had fought in the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) and the War of Liberation (1946-49), came to Hangzhou and found a job as a water-bearer. He would place a piece of flat wood on the top of the pails to prevent the water from spilling while walking, a routine little Wu found quite intriguing.

"The war veteran liked me. He was illiterate and hence, would ask me to make information cards to record the prepayment of his customers. He earned 0.01 yuan ($0.0015) for every pail of water he delivered and gave me 0.01 yuan for every 20 cards I made. I would go watch a film whenever I saved 0.05 yuan," the artist says, adding that earning pocket money at 9 was "unspeakable happiness".

Wu believes the Grand Canal has had a contrasting fate compared to the West Lake, one of the more famous scenic attractions in Hangzhou, which was supported by emperors, generals and poets across dynasties.

"The West Lake was seen as a picturesque asset that needed to be cared for. But the Grand Canal is like our mother. She has watched us grow up, earn a living along her busy banks, leave her in search of a better future and return to her embrace later on," he says.

Yang Jianxin, former director of the culture department of Zhejiang province, paid an apt tribute in the preface of the picture book Charm of the Grand Canal in Hangzhou published by Wu. "The connection between Hangzhou and the Grand Canal is as inseparable as fish and water. … This is not only because the southern end of the canal flows through half of Hangzhou, but also because it records the history of the city and carries its culture."

Wu has created several collections of canal paintings, such as Eight Scenes of Hangzhou and Xiangfu Flower Festival, and published dozens of books, including Civil Life at the Southern End of the Canal and Painting the Canal.

He also led a team all the way north, creating a panorama of folk customs that prevail along the canal. The spot visit and sketching project lasted for over a year.

Recently, Wu completed a 100-meter-long scroll painting of the canal's Tangxi-Xixing stretch in Hangzhou. He is currently working on another equally long scroll painting in the east and west of Zhejiang province. He will finish it by the end of next year.

"I have actually walked the whole length and painted the entire Grand Canal in Hangzhou, borrowing historical anecdotes from every dynasty," Wu proudly says. "The story of the canal needs to be told and the culture it represents must be passed down."

If you have any problems with this article, please contact us at app@chinadaily.com.cn and we'll immediately get back to you.

play

play